One of the most significant side effects caused by the removal of any restrictions upon transfers is the increasing number of athletes that choose to leave their current school for one with more prestige, i.e. move from a university in a non-power conference to one inside one of said power conferences. Or perhaps a lower mid-major to a higher mid-major.

It’s a simple and logical process. A once-overlooked athlete proves their value at a smaller school which finally grabs the attention from the bigger schools that didn’t offer them a scholarship out of high school.

The introduction of NIL to this equation has only inflated the number of transfers. Along with being able to play at bigger schools in front of bigger crowds and on bigger TV stations, there’s quite a big paycheck coming the athlete’s way as well. Some athletes that previously wouldn’t have considered transferring even with the potential jump in exposure and being on a national stage, are now easily coaxed away by the prospect of adding an extra comma or two to their bank account.

But what’s happening to these athletes that make the move up? Are the greener pastures actually green? An attractive narrative that fans, especially those from mid-major schools that are losing all their great athletes to top-tier schools every year, is that failure is very common. The idea is that if you transfer up, you won’t get the same minutes or role as with mid-major schools.

Examples of this aren’t too hard to find. Take the case of Nate Calmese, who averaged 17 points per game and was Southland Freshman of the Year for Lamar men’s basketball in the 2022-23 season. He transferred to Washington and proceeded to appear in less than half of the Huskies’ games and scored 66 points all year (he had 547 in one season at Lamar).

There’s also the somewhat comical career path of Tanner Holden who became a star at Wright State, averaging 20.1 points in the 2021-22 season and then transferred to Ohio State. In one season there he appeared in 27 games but was a bench player who didn’t even put up a shadow of his old numbers. Holden then transferred back to Wright State and finished his career with a solid senior season on par with his previous years with the Raiders.

The not-so-secret hope of fans is that athletes will consider the supposed likelihood of seeing a sharp decrease in playing time will factor into their decision to leave or, better yet, convince them to stay.

But let’s look at the numbers to figure out what’s really going on with the players who decide to transfer “up” and see if this is actually what happens. There are plenty of Calmese’s and Holden’s, but mixed within that are massive success stories, such as Dalton Knecht who transferred from Northern Colorado (and before UNC was in the junior college ranks) to become a consensus All-American at Tennessee.

We’re going to stick with men’s college basketball on this one because that’s what I crunched the numbers on. Said number crunching was me scanning through the 2022-23 season and creating a list of every player at a mid-major school that scored at least 450 points that season (which pretty much comes out to at least 13 points per game).

What did I classify as a “player at a mid-major school”? Anyone who didn’t play for a team in one of the six consensus power conferences, i.e. the ACC, Big 12, Big East, Big Ten, Pac-12, and SEC. I also excluded Gonzaga as a mid-major but designated every other WCC team as a mid-major.

I then went through, athlete by athlete to see who stayed and who transferred and weeding out anyone who graduated or declared for the NBA and thus didn’t play at the NCAA level in the 2023-24 season. I then compared how each person did in the ’23-24 season to how they did in ’22-23.

The three main numbers analyzed were: 1) The percentage of games started by the player for his team; 2) The player’s average minutes played; 3) Their average points per game.

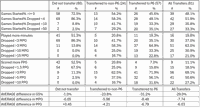

After breaking it all down, comparing how athletes who did and didn’t transfer performed between the 2022-23 and the ‘23-24 seasons, the conclusion is fairly easy to come to:

Athletes that transfer face a high likelihood of seeing some decrease in production and playing time, but are relatively unlikely to see a catastrophic drop in production and should expect to see the floor consistently, often still being a full-time starter.

Here’s the date in table form

Starting with players that didn’t transfer, the variation between seasons can be almost entirely chalked up to random variance that any population will see. Virtually every player started essentially the same number of games, had minimal changes in minutes per game and scored at similar rates.

Pretty safe to say that sticking around give you a very, very high chance of putting up great numbers again.

For the transfers, it’s a lot less safe of a bet. The closest to a certainty they’ll get is essentially a 50/50 shot at starting the same number of games as the previous year. A maybe notable trend is that those transferring to another mid-major school get a slightly better than 50/50 shot and those transferring into the P6 ranks get slightly worse than coin flip odds.

When it comes to everything else, things get more dicey. Barely more than a third of transfers to P6 teams saw better than a minimal drop in minutes per game and only 16 percent had their points per game drop by less than 1.5. Transfers to other mid-major schools have slightly better odds, but both are still far from decent.

So does the data back up what fans often say about guys transferring up? Well, kind of. It’s pretty clear most guys don’t become Dalton Knecht, but not many are a Tanner Holden. They’re more like Jameer Nelson Jr. who starred at Delaware, peaking at 20.6 points per game his final year there, but transferred to TCU. He dropped from 35.2 minutes per game down to 25.0 but started 22 of 34 games for the Horned Frogs who made the NCAA Tournament out of the Big 12. He averaged a solid 11.2 points and 3.3 assists on shooting numbers consistent with his time at Delaware (and George Washington before that).

The question is whether this kind of transfer is worth it. Money alone won’t make things worthwhile and there’s as many examples of that principle as there are dollars heading into the bank accounts of these athletes. Is it worth going from being a star to just a cog in the machine? Probably, so long as that same player is on a more successful team. Nelson likely had few qualms about making that sacrifice given he went from a team that was barely above .500 in a program that’s made the NCAA Tournament twice this century and then found himself on a 21-win squad that made it to said tournament without too much fuss.

But if, let’s say, Nelson had any ambitions to live up to his namesake and make it to the NBA, moving to TCU may not have helped. Chances to showcase his skills were fewer, given the drop in minutes and role, and there’s no evidence to suggest you have to play for a big school to get seen in the draft process.

So long as free and unrestricted transfers, along with NIL inducements, continue to be part of the recruiting process, we’ll continue to see this trend. Athletes will be enticed by promises of money and fame. The money will always be there, but there will always be the risk of not finding the glory and fame.